The Como Recycling Facility is one of the facilities that process waste managed by the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Minn., on April 10, 2024. | Photo by Rosalind Ding

By Rosalind Ding, Ethan Fine, Gabriel Matias Castilho and Isabella Terzian

In the 2023-2024 academic year, the University of Minnesota’s Twin Cities campus had almost 55,000 enrolled students and over 25,000 faculty and working staff.

According to Nick Kluge, UMN department manager of waste recovery services, the university produced 2,416 tons of waste in the first half of the 2023-2024 academic year.

Around 10% of the waste is considered hazardous and requires special procedures for its disposal, including shipping it to specialized facilities across the country, said Adam Krajicek, director of the university’s environmental health & safety department.

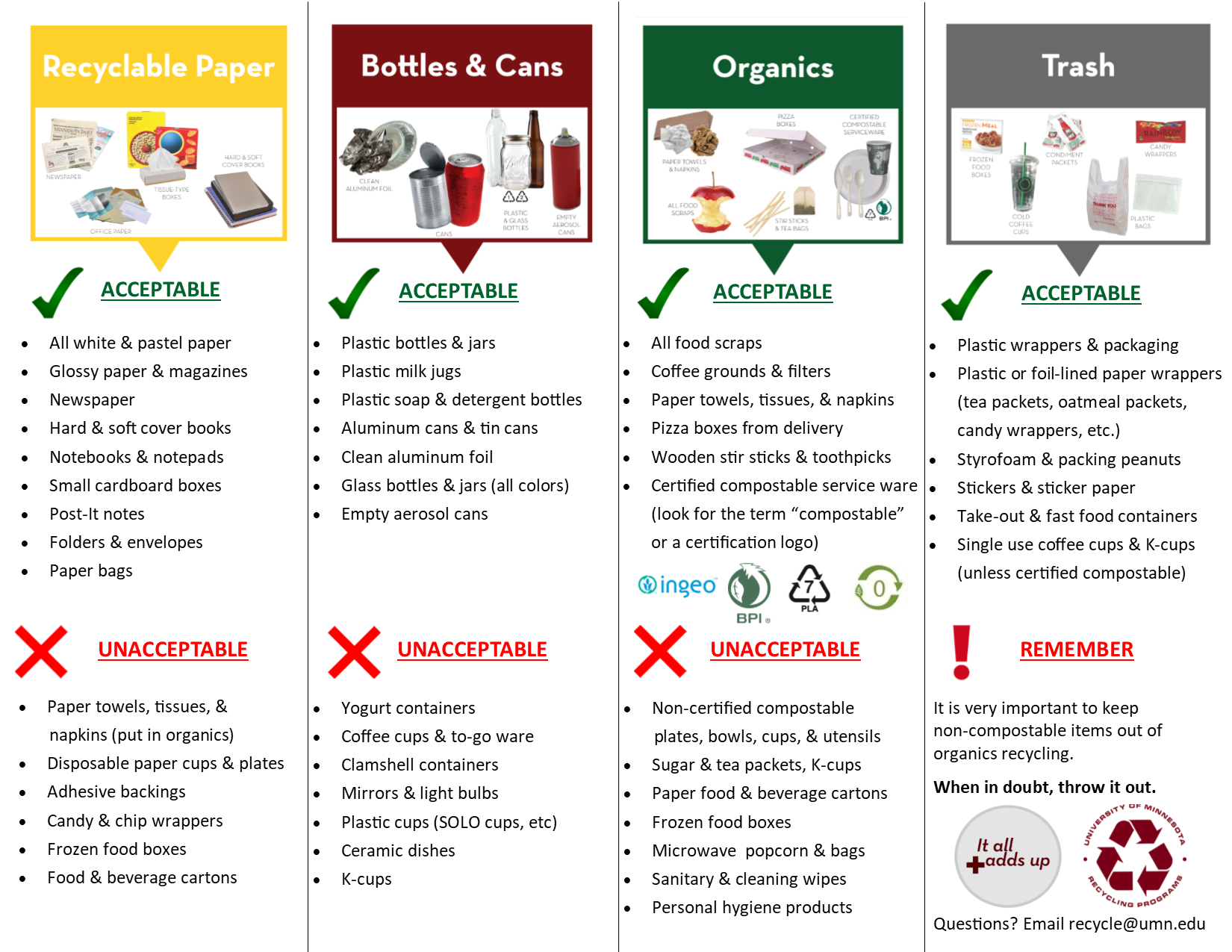

The other 90% are required to be separated into four categories before collection: organics, cans and bottles, recyclable paper, and trash, separated by color.

After throwing the trash out into the trash can, the waste is directed to different facilities for either recovery or disposal.

According to Nick Kluge, around half of this waste gets recycled at the Como Recycling Facility, a university-owned building where recyclables are hand-sorted, audited, and reused to be manufactured into new products.

Organics are sent to an industrial compost site in Rosemount, Minnesota to be transformed into mulch and distributed to local stores.

The final waste, unfit for reuse and recycling, is incinerated at the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center (HERC), a waste-to-energy facility at the heart of Minneapolis. This corresponds to around 45% of the total waste produced, according to the University of Minnesota.

This recovery center recently became the target of protests and faced scrutiny by multiple environmental activist groups.

On October 24, 2023, the Hennepin County Board passed a resolution asking for the development of a HERC closure plan between 2028 and 2040 by February 1.

On January 19, David Hough, Hennepin County’s county administrator, and Lisa Cerney, Hennepin County’s assistant county administrator for Public Works, wrote in a memo to the Hennepin County Board of Commissioners that the timeline for reaching an 85% recycling rate by 2028-2040 was unrealistic and a closure time frame would negatively impact environmental justice.

Environmental and social justice activist groups said the Hennepin County leaders’ plan to operate the facility for another decade was unacceptable, according to the Star Tribune.

Meanwhile, the UMN Interim President approved the Climate Action Plan (CAP) in February 2024, aiming to become carbon neutral by 2050 and dividing emissions into three scopes, depending on whether they are directly emitted by a university-owned building, purchased or from indirect sources partnered with the university.

The UMN’s CAP focuses on five sectors for climate mitigation: heating/cooling, fleet, air travel, electricity and commuting.

Waste management is not accounted for in the CAP because it was hard to obtain, according to the university.

Exploring the HERC

In the 1980s, lawmakers passed legislation that left landfills abandoned in search of a better alternative, said Paula Pentel, coordinator of the Urban Studies program at UMN.

Landfills often pollute groundwater and create large amounts of residual waste. Incinerators, on the other hand, are quicker and reduce the amount of space taken up by trash, according to a report from the University of Toronto.

However, incinerators also come at a price. Burning trash is costly, both monetarily and to human health. Incinerating trash can emit toxic chemicals, heavy metals, and particles, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Minnesota currently has the third-most active Municipal Solid Waste incinerators in the country, according to the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

Established in 1989, the HERC serves the Minneapolis community as the primary location for incinerating waste. It features two units that can each burn up to 606 tons of waste per day and has a permitted mass burn capacity of 365 thousand tons each year.

An estimated 2,250 tons of that waste comes from the University of Minnesota.

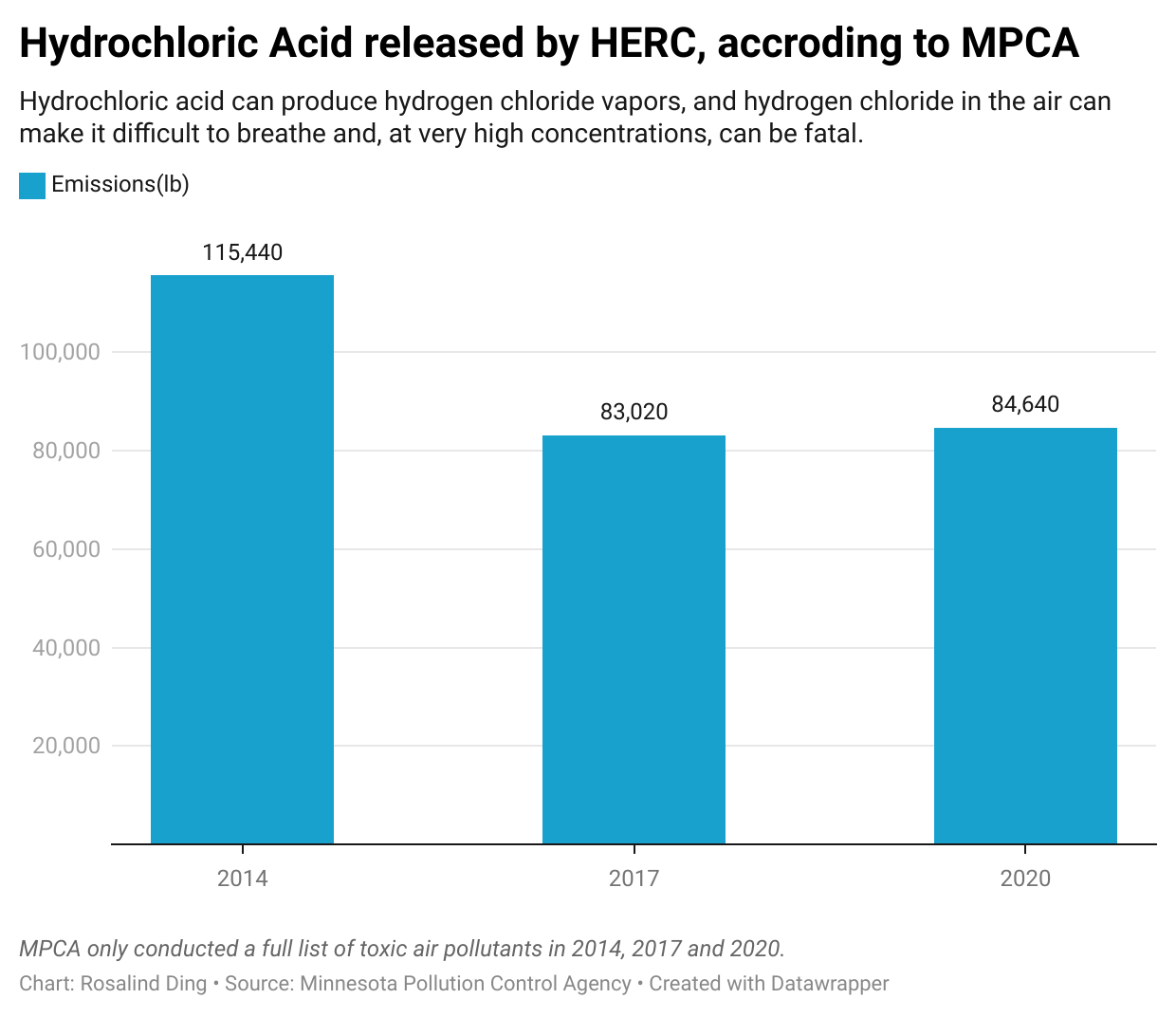

The HERC is only required to release data on all emissions from the plant every three years. Every other year, the HERC releases select emissions data.

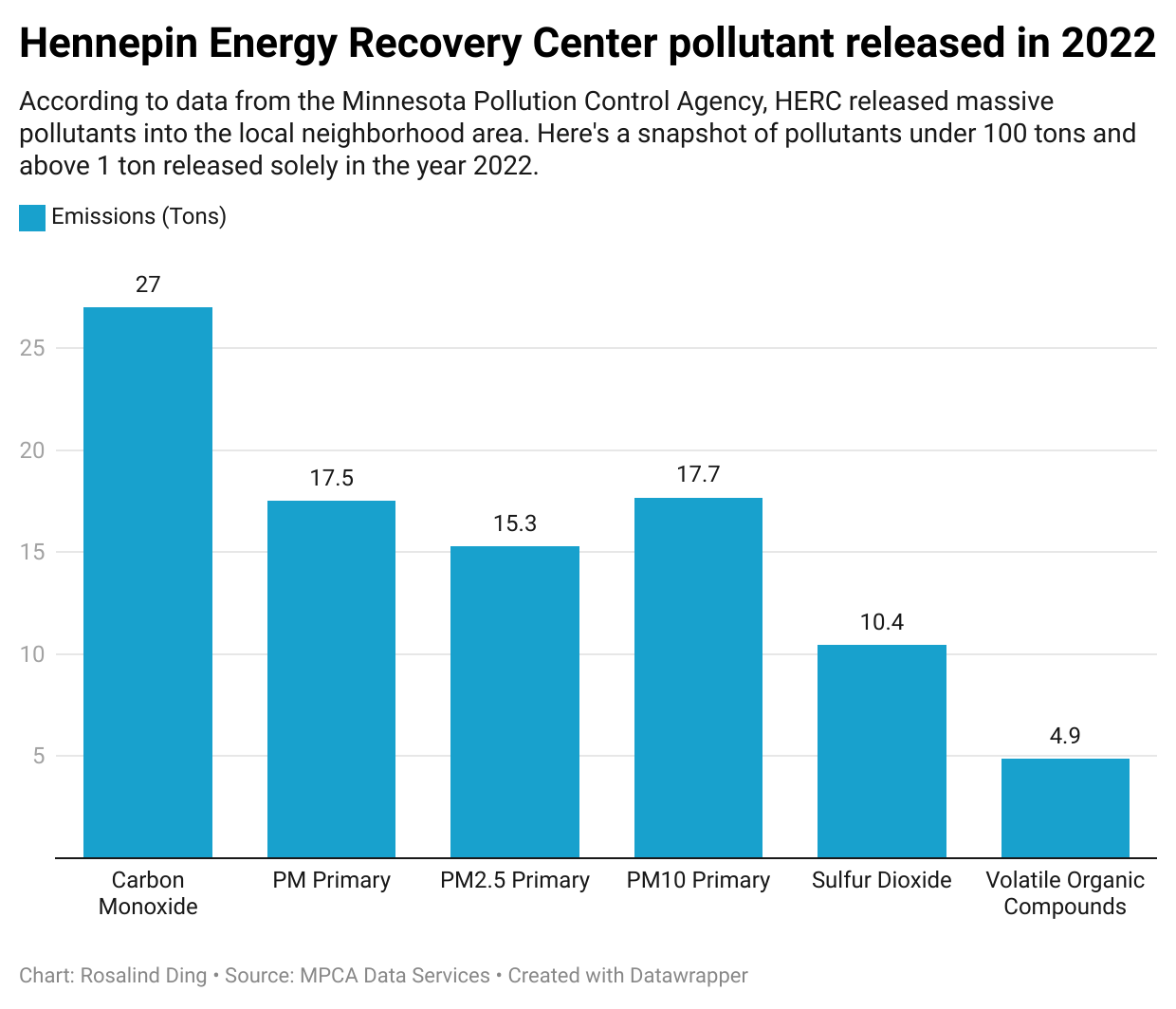

In 2022, the most recent year of data to be released, the HERC emitted over 70 million pounds of CO2-equivalent gases and almost 50 thousand pounds of carbon monoxide into the atmosphere, according to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

The facility also emitted particle matter (PM) in high amounts and kept track of the size of those pollutants. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, PM is a complex mixture of air-borne particles and liquid droplets composed of acids, ammonium, water, black carbon, organic chemicals, metals, and soil material. It can be divided into PM 2.5, “fine particles” such as those found in smoke and haze that have diameters less than 2.5 microns; or PM10, “coarse particles” including all particles less than 10 microns in size.

In 2020, the last time the HERC disclosed all emissions data, the facility emitted 84,640 pounds of hydrochloric acid.

According to the MPCA, the HERC is currently the largest emitter of toxins in Hennepin County and one of the biggest contributors of almost all criteria pollutants.

The Health Risks

More than 230 thousand Minnesotans live within a three-mile radius of the seven incinerators in the state.

However, the HERC, located in North Minneapolis, is a major point of concern regarding health hazards for nearby residents.

Loretta Akpala, a resident physician at a north Minneapolis clinic, said the HERC’s incinerator toxic emissions disproportionately affect low-income and minority communities in the area. This raises health concerns about environmental justice and health equity, according to MPR.

The Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, an environmental activist group, published a report saying particles emitted by the incinerator are linked to respiratory diseases like asthma, prevalent in the local community. These individuals also experience higher rates of hospitalization.

Emissions from the HERC contribute to about $16 million in health damages and around 2 air pollution-induced deaths per year in Hennepin County. The proximity of the facility to dense residential areas exacerbates these health risks.

Disparity

Some neighborhoods are more burdened.

According to the Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, the area within a three-mile radius of the HERC plant has a higher proportion of low-income households and a greater percentage of people of color than most of the state.

Maari Booker, a North Minneapolis resident, said in a Kare11 interview that all of the sources of pollution, not only the HERC but also the I-94 traffic and Minneapolis Highway 55, have a cumulative effect on area residents.

This health hazard is compounded by economic vulnerabilities that exacerbate disparities, as lower-income families often lack access to healthcare and resources to counteract pollution effects, according to the National Library of Medicine.

East Phillips resident Antonio Diaz said the disparities related to the placement of the HERC and other facilities “are directly related to race.”

Diaz feels intentionally uninformed by the city.

“They just, like, did a lot of things to mislead the community,” he said.

He also said, in contrast to the previous statement, that he is often surprised by the knowledge he gets from local protestors and organizers who voice their concerns and objections to facilities such as the HERC that produce dangerous emissions.

“I just haven’t had a lot of capacity to inform myself, I guess. But I trust the people that I am in community with.”

Antonio recounts an instance where the city planned to tear down a nearby building called the Roof Depot.

“There were lots of protests, organizing, and energy that went into just saying ‘Hey, don’t poison our neighborhood,’” he said.

Diaz said that tearing down the building would have released asbestos into the air and groundwater near East Phillips and other low-income BIPOC neighborhoods.

“It was something that, like, happened because of the community,” Diaz said. “The city would have easily been fine with poisoning, and kind of, murdering Black and brown people.”

He worries about the safety of drinking water in the future for his community.

“I’m concerned about the water. Minneapolis water has, like, consistently been safe to drink, which is just like, a basic human right, and I don’t wanna see that taken away.” Diaz said.

Diaz said he wishes to see changes to more responsible leadership and policymaking and hopes cities will advocate for the less privileged and hold themselves accountable.

Educational initiatives, public meetings, and protests have been essential in raising awareness and pressing for policy changes. These efforts underscore the community’s resilience and determination to hold policymakers accountable and to advocate for a healthier, more equitable environment.

A Broader Pattern of Injustice

The placement and operation of the HERC highlight a broader pattern of environmental injustice often seen across the United States, where industrial facilities are disproportionately located in low-income and minority communities.

According to MinnPost, in North Minneapolis, where the HERC is located, nearly half of residents lived below the poverty line in 2018, compared to 36% of families in other parts of the city.

The Metropolitan Council reports that in Minneapolis and Saint Paul, the combined poverty rate exceeds double that of the region’s suburban and rural communities.

The North Loop neighborhood had its poverty rates decreased from 36% to 15% in the last 40 years, MinnPost reports. This neighborhood is constructed of housing for wealthy families, with high-rise apartments and condo buildings.

However, North Loop’s demographic and housing is an exception to the usual lower-income housing surrounding the facility.

What unites all neighborhoods is a lack of information and awareness from residents and business owners of what the HERC is or what risks associated with its processes are.

The controversy regarding the HERC’s impact includes discussions on its contribution to climate change. According to the Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, there are more innovative and effective ways to process trash and waste than through an incinerator, such as recycling and composting.

University Efforts

With all of the issues surrounding the possibility of a closure of the HERC facility, the University of Minnesota, which diverts almost half of its waste to the incinerator, prepared its new Climate Action Plan.

The plan prioritizes reducing energy usage on campus and increasing the supply of renewable energy. This includes efforts to decarbonize campus heating, cooling, and power generation systems, possibly through electrification and geothermal district systems.

Another focus is on sustainable transportation solutions. This encompasses efforts to decarbonize the campus fleet, reduce emissions from commuting, and create incentives for low-carbon commuting options. Strategies are being developed to right-size and electrify the fleet of vehicles and to enhance infrastructure for electric vehicles.

The University is developing programs for carbon offsets, especially targeting emissions from university-sponsored travel. This includes evaluating and potentially restructuring travel policies to reduce the overall carbon footprint associated with official travel.

The plan also involves engaging the university community through workshops, surveys, and other activities to gather input and build consensus around sustainability initiatives. The emphasis is on integrating sustainability into the curriculum and research activities to foster an educational environment that supports the university’s climate goals.

Though the University has chosen to focus its plan on greenhouse gas emissions rather than waste, programs like the Student Sustainability Advocates and the Green Labs Program encourage students to take active roles in reducing campus waste and promoting sustainable research practices.

The university has initiatives such as Opt-in Organics, a waste recovery program that helps the university hold the highest waste diversion rate in the Big Ten, recovering more than 55% of waste from entering landfills.

Building on its achievement of having the highest waste diversion rate in the Big Ten, the waste management efforts are directed towards zero waste initiatives and enhancing recycling programs on campus.

The Environmental club program encourages students to engage directly in sustainability efforts that range from organic waste programs in residence halls to advocating for broader institutional change through communication with local representatives.

Ella England is a senior student in the UMN environmental club and a sustainability studies minor. She hopes to go into environmental policy in the future, a career she hadn’t aspired to before attending the University of Minnesota.

The interdisciplinary sustainability studies minor allows students to explore real-world environmental problems from multiple academic perspectives.

“[In environmental club] We’ll do small things like painting plant potters that kind of incentivize people to come to the club, but at the same time use that engagement to encourage students to advocate for the planet and educate them on why, how, etc,” England said.

The university hosts various events and programs that provide platforms for students to learn about and get involved with sustainability practices on campus. An example of one of these programs is the Sustainability Coffee Chats series.

The Sustainability Coffee Chats engages the University of Minnesota community in discussions about campus sustainability to increase awareness and encourage collaboration across campus organizations. University and community experts present various topics at these events to enable conversation about different aspects of sustainability.

Student-run organizations such as the Indigenous Environmental Network prioritize collaborations with environmental non-profits and indigenous organizations, aiming for legislative changes towards clean energy and transportation.

The University of Minnesota offers programs that directly address and engage with sustainability topics. These majors include Environmental Sciences, Policy, and Management in the ESPM undergraduate program, as well as a Master of Science, Technology, and Environmental Policy.